A Tale of Two Copyright Offices: Copyrightability of AI-Generated Works Under UK and US Copyright Laws

I. Introduction

Since the introduction of The Statute of Anne in 1710 in the United Kingdom, the first copyright statute providing protection to literary works, copyright law has faced numerous challenges and evolved in a way to respond to them, which resulted in accommodating more works within the copyright law sphere.[1] Invention of the photography machine, the emergence of the film industry, the possibility of transmitting electrical signals, radio or television programmes from one place to another have all played a role in the development of copyright law, changing its scope from merely protecting literary works to protecting various works, such as artistic, musical, and dramatic works, as well as films, sound recordings, and broadcasts.[2] Besides experiencing gradual expansions regarding the protectable subject matters, copyright law has also evolved in such a way to provide longer terms of protection and wider rights to be enjoyed by the authors of protectable subject matters.[3] It is therefore not uncommon for copyright law to be subject to calls for change, and respond to some of them, as the means of creation evolve and the awareness of artists and authors increase over time.

In light of this, generative AI (GenAI) technology is no exception to the developments initiating a change in copyright law. The prevalent use of GenAI in the creative industries and by creative individuals,[4] raises numerous concerns at the various stages of the creative process.[5] It first questions the pre-creation phase of individuals and causes us to reconsider how, why, and under which circumstances individuals can produce creative works, and compare this process to the training stage of GenAI tools. It then casts doubts on the copyrightability standards and whether they still make sense in a highly digitised world or whether we need to adopt more flexible approaches and interpretations in deciding the copyrightability of a content, especially when GenAI is used in its creation. Finally, it poses the crucial question whether the copyrights of authors whose works were used or reproduced in the final AI-generated output is infringed.

This article will look into the second issue by reference to two jurisdictions which have been struggling with that question for some time: the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US). UK copyright law provides protection to “computer-generated works”[6] which also covers AI-generated works. However, very recently, the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) issued a Consultation,[7] seeking opinions on many aspects of the use of GenAI technology in the creative industries, including whether its provision providing protection to such works is causing confusion instead of clarification. While the UKIPO Consultation was running, the US Copyright Office (USCO) released a Report,[8] demonstrating its stance towards the copyrightability of AI-generated outputs, and rendered a remarkable decision to protect an AI-generated work.[9] Accordingly, after providing a brief overview of UK and US copyright laws, all these developments will be critically evaluated in detail in this article to see if AI-generated works can be copyrightable.

II. Brief Overview of UK and US Copyright Laws

There are several theories aiming to justify the existence and necessity of copyright law. Some of them state that it is a natural property right arising from the fact that authors create something that did not exist before by applying their labour to the ideas and items common to all.[10] This “sweat of the brow” approach, although largely abandoned now, prioritises the efforts of authors and artists, and justifies protection on the basis of these efforts. The incentive theory, on the other hand, supports that creative individuals should be rewarded for their creative endeavours in order to both encourage them to continue creating works that would benefit the society in general, and allow them to obtain a remuneration for their creative efforts.[11]

Although UK copyright law had reflected the “sweat of the brow” approach for a long time, due to the case law created by the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU), it started placing more emphasis on authors’ creativity – rather than their labour – in the production of a work, for the past decade.[12] The US, likewise, shifted away from an efforts-based approach to a creativity-centred one in early 1990s.[13] Despite following roughly the same theoretical underpinning for justifying copyright law, the UK and the US have some non-negligible differences in providing copyright protection to works, which seem to have broader implications regarding the copyrightability and infringement issues arising from AI-generated works, and therefore, worth exploring in the subsections below.

a. Copyrightability Requirements in the UK

In the UK, as in most jurisdictions, copyright protection is automatically provided to works satisfying certain criteria, without the need for registration at an intellectual property or copyright office. According to the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA), to be eligible for copyright protection, a content must, above all, fall within one of the eight categories provided therein.[14] Depending on which category it falls, it might also be asked from a work to be original.[15] It is also required from authors to fix or record their works in some material form, in accordance with Article 2(2) of the Berne Convention,[16] an international agreement setting the minimum thresholds for the protection of literary and artistic works. Works meeting these conditions are protected for the duration of the author’s lifetime and 70 years thereafter,[17] and the authors of such works are provided with various economic rights, including the right to reproduce (copy) the work,[18] and some moral rights to attribution and object to derogatory treatment.[19]

While providing extensive protection to authors and artists, UK copyright law also recognises numerous exceptions to their rights,[20] allowing room for the public or other artists to use some parts of copyright works, without being required to make licensing agreements and royalty fees, in certain specific cases. This is mainly to establish a “fair balance”[21] between the interests of authors in protecting and benefitting from their works, and interests of users in using extracts from those works in creating new content. It can clearly be observed from the exceptions that they serve the fulfilment of certain fundamental rights, such as the freedom of expression by criticising or reviewing a work,[22] and freedom of the arts by producing parodies of copyright works.[23]

Alongside the abovementioned protection provided to certain works, UK copyright law has a unique provision directly addressing works generated by computers, and thereby AI.[24] The relevant provision reads as follows: “In the case of a literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work which is computer-generated, the author shall be taken to be the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken”. Although the provision has a few aspects causing ambiguity regarding whether the provision has any merit or whether it can achieve what it seems to intend, which will be discussed in the next section, for now, it suffices to say that UK copyright law is not against the protection of original literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works, even when GenAI tools are involved in their creation.

b. Copyrightability Requirements in the US

Copyright protection in the US also arises automatically, however, for authors to enforce their rights, in other words to claim copyright infringement before the court, they need to have their works registered at the USCO.[25] This means that in the majority of the cases, it will be the USCO to decide whether a certain work meets the necessary requirements of copyrightability and provide the title of authorship to the creator of the work. For the USCO to find a work copyrightable, the work needs to demonstrate the necessary degree of originality and should meet the fixation requirement. Unlike the UK, US copyright law does not require works to be classified within one of the pre-set types of works. The US Copyright Code merely identifies some examples that might benefit from copyright protection but in no way imposes a restriction on the types of works that can receive copyright.[26] Thus, the only requirements that works need to satisfy are being original and “fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed”.[27] Once works meet these criteria they receive copyright protection for the same duration as in the UK, i.e., author’s lifetime plus 70 years after the author’s death.[28] And although authors in the US also enjoy various economic rights,[29] they almost never[30] have moral rights.

Again, with similar concerns in mind as the UK, the US copyright law recognises the importance of allowing for some room in which third parties could freely use existing copyright works without the need for obtaining an authorisation or a licence. However, differently from the UK, US copyright law does not provide a closed list of exceptions. Similar to the manner it illustrates some copyrightable works, it identifies some exemplary instances of fair use and factors that need to be taken into account in order to decide whether an unauthorised use of a copyright work can be “fair”, without providing an exhaustive list of permitted acts.[31] Therefore, whether a certain unauthorised use of a copyright work is fair, and thus not infringing, is decided on a case-by-case basis by the courts.

The US does not have a specific provision dealing with the copyrightability of AI-generated works, however, the USCO has recently published a Report explaining its stance on providing copyright protection to works created with the involvement of GenAI technology.[32] Although this Report does not have legislative authority because of not being adopted by the Congress, and therefore is in no way binding upon the courts, the USCO’s consistent application of its ideas might influence – if had not done so already – the courts. It may thus be possible to argue that US is in the process of making law that excludes works that are generated entirely by AI tools.[33]

Having demonstrated the fundamental principles of copyright law in the UK and the US, as well as mentioning these jurisdictions’ approaches to AI-generated works briefly, it is now time to explore in detail the conditions under which UK and US are likely to provide such works copyright protection.

III. Copyrightability of AI-Generated Works

There is not much debate whether GenAI tools can produce works that highly resemble the types of works, such as literary, artistic, and musical, that usually qualify as protectable subject matter under copyright law. It is also not disputed whether they meet the fixation requirement as they are recorded or fixed in a material form. The only remaining issue that cause copyright offices or courts to deny protection to such works is failure to meet the originality criterion.

a. UKIPO’s Stance

In the UK, following some landmark decisions of the CJEU, it is required from works to be “author’s own intellectual creation”,[34] result from author’s “free and creative choices”,[35] and bear the “personal touch” of authors.[36] It is apparent that, by defining originality with explicit references to the author, and by emphasising certain features which can only be exhibited by humans such as creativity, free choice, and personal touch, an implicit link between the originality criterion and a human authorship requirement has been established. In other words, the originality criterion does not only ask the work to demonstrate certain features, but also requires the work to emerge from a human making creative choices. Furthermore, the UK, even post-Brexit, is to continue following this interpretation of originality, as recently stated by Lord Justice Arnold in THJ v Sheridan.[37] It thus follows that an author claiming copyright for a work generated with the involvement of GenAI tools needs to demonstrate a sufficient level of human creativity in the final product.

Against this background, the specific provision of CDPA s. 9(3) might be considered relevant or perhaps even helpful as it clearly acknowledges that works generated by AI are entitled to copyright. Some commentators argue that this provision creates an exception to the originality requirement sought for literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works,[38] and therefore avoids providing an answer to the highly controversial question of how a work generated by a computer can demonstrate humane features, such as creativity. Others argue that the provision does not create an exception to the originality requirement but creates an inherent inconsistency as it is challenging to consider AI outputs as satisfying the “author’s own intellectual creation” standard.[39] It might be possible to argue that a computer-generated work, which lacks a human author as defined by the CDPA s. 178, would obviously lack human intellectual creation. However, if this were the case, s. 9(3) would have been contrary to the foundational principles of providing certain works with broad monopolistic rights as it would have protected even the most ordinary and banal artistic or literary AI-generated works that do not involve any creativity or imagination. Neither the Lockean theory, nor the incentive theory would support such conclusion.

All this ambiguity regarding whether s. 9(3) requires originality perhaps arises from the spurious distinction[40] introduced by that provision and reinforced by the definition of “computer-generated” works in s. 178. As recently stated by the UKIPO in its Consultation, s. 9(3) applies to entirely computer-generated works, while computer-assisted works are still protected under CDPA s. 1(1)(a). This interpretation of the provision is highly problematic. It is not always easy or possible to distinguish works generated by GenAI tools from works created by a human who merely sought the assistance of those tools. Attempting to identify the level of AI involvement and categorising the final product depending on the significance of that involvement seems to require technical knowledge as well as a deep understanding of the black box nature of GenAI tools. These tasks, however, are clearly beyond the scope of the assessment that copyright lawyers are qualified for. Moreover, this would result in a deep investigation into the creative processes of authors which is alien to copyrightability assessment. Copyright law should only be concerned with protecting creative expressions, and the assessment should not be diluted by making judgments on the creation means and processes of authors.[41]

The UKIPO, probably having some of these concerns in mind, suggested removing s. 9(3) from CDPA and stated that it would not make a difference as there is not sufficient evidence demonstrating the usefulness of the said provision.[42] Although it might be true that the UK courts have not yet faced a lawsuit concerning the copyrightability and originality of AI-generated works,[43] abandoning the availability of a protection to AI-generated works can create a crucial misunderstanding that the UK will no longer include AI works among the copyrightable subject matters.[44] The UKIPO argued that AI-assisted works would still be protected under CDPA s. 1(1)(a) as long as they are original. However, it is highly unlikely that authors and artists will be aware of this minor nuance the UKIPO is attempting to introduce between AI-assisted and AI-generated works and could therefore believe that GenAI tools should no longer be a part of their creative processes if they want to secure copyright protection in the UK. The better approach in resolving the uncertainties is, as suggested elsewhere,[45] (i) abandoning the distinction (which does not have an explicit legislative foundation as the CDPA does not mention such distinction) between AI-assisted and AI-generated works, and (ii) clarifying the meaning of “computer-generated” in s. 178 by upholding the originality requirement for AI creations.

While the UK has the necessary legislative tools to provide copyright protection to AI works, the UKIPO seems to act with caution in doing so by trying to impose a spurious distinction depending on the level of AI involvement in the creation of a work. However, if, instead of attempting to introduce inherently alien and arbitrary standards to copyright law only for deciding the copyrightability of AI outputs, a more systematic approach of looking for originality in those works is adopted, then the UK can truly become a jurisdiction that is welcoming emergent technologies and new methods of creation. It might be possible to seek the originality of works created by GenAI tools in the human-generated aspects of them, namely, in the prompts triggering the creation of the work[46] and further instructions given to these tools upon their creation of an initial output.[47] Sufficiently detailed and original prompts and instructions should render works generated upon them original and therefore, copyrightable under UK copyright law.

b. USCO’s Approach

Moving on to the US approach to the issue of copyrightability of AI outputs, roughly the same points made for the UK can be re-stated: It also attempts to introduce a distinction between AI-generated and AI-assisted works[48] and rejects the originality of wholly AI-generated works due to lack of sufficient human authorship.[49] However, unlike the UKIPO, USCO explicitly comments on and rejects the appropriateness of prompts for ensuring originality of the AI output.[50] According to the USCO, prompts alone are not sufficient to render the AI-generated work original because inter alia GenAI tools can sometimes add elements to the final work, which were not asked for or thought about by the users. In other words, USCO believes that the black box nature of the technology prevents users from exercising sufficient amount of control over the final product, leaving room for the GenAI tools to act arbitrarily and generate unexpected elements, which eventually prevents it from labelling a person as the human author.[51] Furthermore, the USCO had already began making decisions based on these same assumptions and arguments, and had been denying copyright protection to numerous AI-generated outputs due to lack of sufficient human authorship, i.e., originality.[52]

Since Feist it has been sufficient to demonstrate a “modicum of creativity” for a work to be original, making it possible to find originality even in ordinary products demonstrating a minimum level of creativity, such as telephone directories.[53] Therefore, especially when compared with telephone directories, it is possible to argue that the USCO should have found originality in at least some AI-generated works. The most well-known AI-generated images that were refused protection are A Recent Entrance to Paradise, Théâtre D’opéra Spatial, and the visual parts of Zarya of the Dawn. In all these cases, the reason for the USCO to deny protection was the so-called lack of sufficient human involvement, control, and creativity, which caused these outputs to fall short of the originality threshold. Moreover, few weeks ago the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit confirmed the finding of the USCO in A Recent Entrance to Paradise by holding that human authorship is a “bedrock requirement of copyright law”[54] and that its absence inevitably disqualifies works from receiving copyright protection.[55]

Although it is reasonable to require a human from whom the work should emerge, the necessary level of originality should not be over-emphasised. As demonstrated above, the threshold for creativity is not set very high. If even a minimum degree of creativity is sufficient for a work to be considered original, then the detailed prompts and instructions provided to the relevant GenAI tools by Jason Allen and Kris Kashtanova in Théâtre D’opéra Spatial and Zarya of the Dawn, respectively, as well as the modifications they made on the initial output generated by those tools to obtain the final product should also have sufficed for human authorship and for a finding of originality.

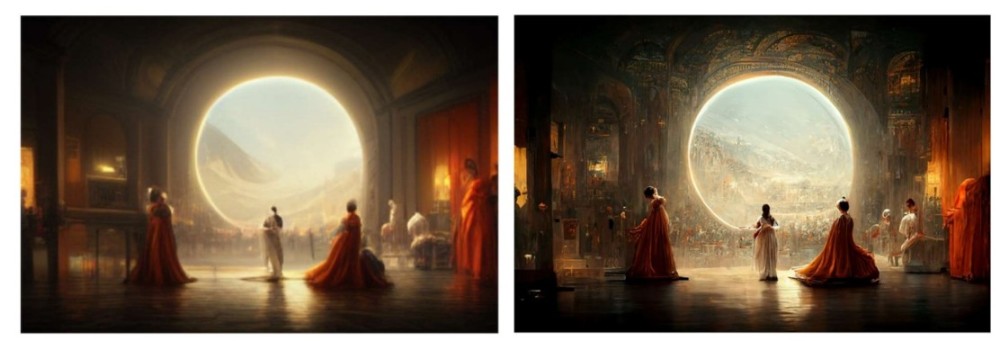

The AI-generated output and the final image (Théâtre D’opéra Spatial) for which Mr Allen was denied copyright protection.

Despite its consistent denial of finding originality in AI-generated images, at the end of January, for the first time ever, the USCO recognised the copyrightability of an AI-generated image named A Single Piece of American Cheese, which was produced by a method called “inpainting”.[56] According to the USCO the author, Kent Keirsey, could demonstrate creativity in the process of “selecting, coordinating, and arranging” the various elements of the image,[57] and could therefore meet the human authorship and originality requirements. However, it should be noted that the USCO implicitly treated A Single Piece of American Cheese as merely a factual compilation,[58] rather than an artistic work. This might be a more material classification than one perceives at first glance, since copyright protection of this image will only extend to the original parts of it, i.e., solely to the “[s]election, coordination, and arrangement of material generated by [AI]”,[59] while leaving the artwork itself outside the scope of protection. Although this approach might be considered as an encouraging and constructive step in terms of responding to technological developments via copyright law, there still seems to be further room for improvement in order not to undermine the aesthetic value of AI-generated art, creative endeavours of AI artists, and the capabilities of the GenAI technology.[60]

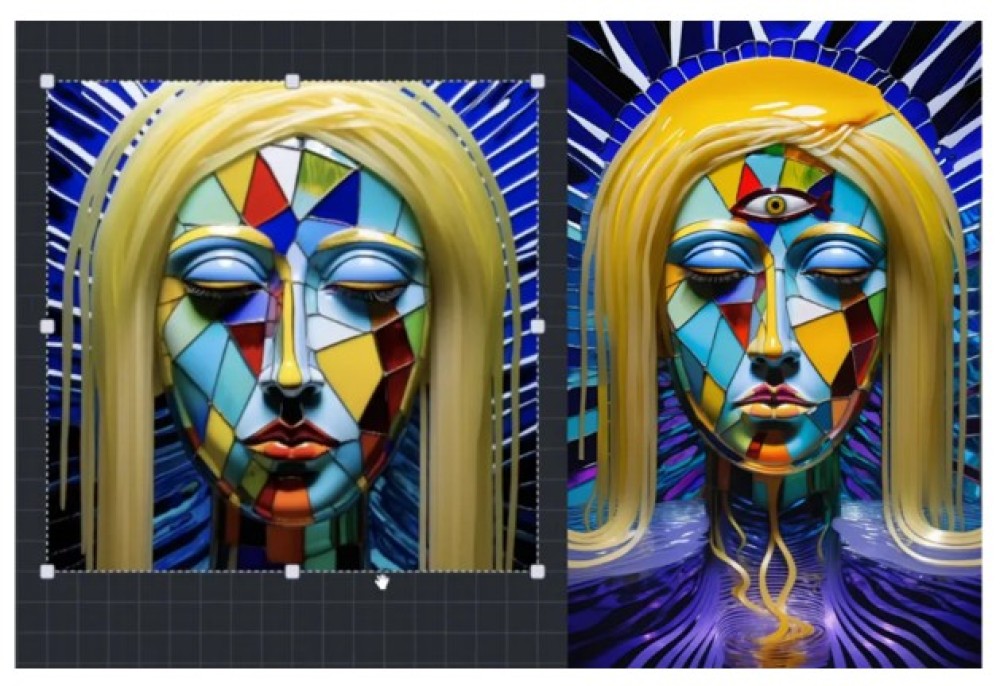

The AI-generated output and the final image (A Single Piece of American Cheese) for which Mr Keirsey was afforded copyright protection.

IV. Conclusion

In sum, both the UK and US copyright law frameworks seem to have the necessary means to acknowledge the copyrightability of certain AI-generated works that meet the existing tests and thresholds of originality. However, for one reason or another, both jurisdictions seem to act with caution, and even consider changing the law in order to exclude such works from copyright. UKIPO’s proposal to remove s. 9(3) from the CDPA might be perceived as an attempt to restrict the protection of AI-generated works, while the USCO’s new stance on the originality of such works can clearly be understood as a limitation on the scope of the copyrightable elements, features of AI creations. Both approaches, however, might undermine the capabilities of the GenAI technology and creative efforts of artists and authors working with this technology.

There is no legal basis for treating AI-generated works differently than traditional works of authorship. As long as they meet the existing requirements for copyright protection, it does not seem justifiable to try introducing new standards or arbitrary distinctions between works that are created by different methods or by using different technological tools. If an AI output demonstrates its author’s own intellectual creation, perhaps in prompts, then it should be eligible for copyright protection in the UK, independent of the degree of AI involvement. Similarly, if a work meets the minimum amount of creativity, which is clearly an easier threshold to meet compared to the UK approach, then there should not be further obstacles preventing it from enjoying copyright in the US. It thus follows that both the UK and US interpretations of originality can be met at least by some AI outputs, which should therefore be protected in the same manner as any other copyright work. Introducing an artificial distinction between AI-generated and AI-assisted works, abolishing explicit protections to AI outputs, or treating AI-generated artworks merely as compilations, collages might result in undermining the value of copyright law as well as doubting its capability and willingness to respond to technological developments.

[1] For some detailed discussions on the development of copyright law resulting in the expansion of the copyrightable subject matter see Elena Cooper, Art and Modern Copyright: The Contested Image (CUP 2018); Laddie J, ‘Copyright: over-strength, over-regulated, over-rated?’ (1996) 18 EIPR 253.

[2] See eg UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (CDPA), s 1(1); 17 US Copyright Code (17 USC), s 102; Turkish Law on Intellectual and Artistic Works, arts 2-5.

[3] Laddie (n 1) 254-257.

[4] See eg Refik Anadol, ‘About Refik Anadol’ (Refik Anadol) <https://refikanadol.com/refik-anadol/> accessed 29 March 2025; Claudia Baxter, ‘AI art: The end of creativity or the start of a new movement?’ (BBC, 21 October 2024) <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/dec/01/six-leading-british-artists-making-art-with-ai> accessed 29 March 2025; Happy, ‘8 Musicians and Producers Using AI to Make Music’ (Happy, 27 June 2024) <https://happymag.tv/musicians-producers-using-ai/> accessed 29 March 2025.

[5] For a tripartite evaluation of copyright law issues arising from GenAI tools and outputs see Eleonora Rosati, ‘Infringing AI: Liability for AI-Generated Outputs under International, EU, and UK Copyright Law’ (2024) European Journal of Risk Regulation <https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/C568C6B717E9CFC45FB52E58E54B6BEC/S1867299X24000722a.pdf/infringing-ai-liability-for-ai-generated-outputs-under-international-eu-and-uk-copyright-law.pdf> accessed 29 March 2025.

[6] CDPA, s 9(3).

[7] The UKIPO, ‘Open consultation: Copyright and Artificial Intelligence’ (GOV.UK, 17 December 2024) <https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/copyright-and-artificial-intelligence/copyright-and-artificial-intelligence> accessed 29 March 2025. The Consultation ren from 17 December 2024 to 25 February 2025 and received more than 11,500 responses from the public.

[8] US Copyright Office, ‘Copyright and Artificial Intelligence Part 2: Copyrightability’ (US Copyright Office, 29 January 2025) <https://www.copyright.gov/ai/Copyright-and-Artificial-Intelligence-Part-2-Copyrightability-Report.pdf> accessed 29 March 2025.

[9] USCO Public Records System, ‘A Single Piece of American Cheese’ (USCO, 30 January 2025) <https://publicrecords.copyright.gov/detailed-record/37990563> accessed 29 March 2025; invoke, ‘How We Received The First Copyright for a Single Image Created Entirely with AI-Generated Material’ (invoke, 30 January 2025) <https://44037860.fs1.hubspotusercontent-na1.net/hubfs/44037860/Invoke-First-Copyright-Image-AI-Generated-Material-Report.pdf> accessed 29 March 2025.

[10] Justin Hughes, ‘The Philosophy of Intellectual Property’ (1988) 77 GeoLJ 287. See also John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (CUP 1988);

[11] Patrick R Goold and David A Simon, ‘On Copyright Utilitarianism’ (2024) 99 Indiana LJ 721

[12] See especially C-5/08 Infopaq International v Danske Dagblades Forening ECLI:EU:C:2009:465 and THJ Systems v Sheridan [2023] EWHC 927 (Ch) for UK’s most recent reaffirmation of EU originality standard.

[13] Feist Publications, Inc v Rural Telephone Service Company, 499 US 340 (1991).

[14] CDPA, s 1(1)(a)-(c).

[15] Originality is only required from literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works see CDPA, s 1(1)(a) cf CDPA, s 1(1)(b) and (c).

[16] Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, art 2(2): “… works shall not be protected unless they have been fixed in some material form”; CDPA, s 3(2).

[17] CDPA, s 12.

[18] CDPA, s 16.

[19] CDPA, s 77 and 80.

[20] See particularly CDPA, s 28-31, 32, and 62.

[21] See eg Case C-476/17 Pelham GmbH and Others v Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider-Esleben [2019] ECLI:EU:C:2019:624; Case C-469/17 Funke Medien NRW GmbH v Bundesrepublik Deutschland [2018] ECLI:EU:C:2019:623.

[22] CDPA, s 30.

[23] CDPA, s 30A.

[24] CDPA, s 9(3).

[25] 17 USC, s 411(a).

[26] 17 USC, s 102: “Copyright protection subsists … in original works of authorship… [which] include the following categories” (emphasis added).

[27] ibid.

[28] 17 USC, s 302(a).

[29] 17 USC, s 106.

[30] Only the authors of works of visual art are entitled to the rights of attribution and integrity, see 17 USC, s 106A(a)-(b).

[31] 17 USC, s 107.

[32] US Copyright Office, ‘Copyright and Artificial Intelligence’ (n 8).

[33] See Section III.b.

[34] Infopaq (n 12) para 37.

[35] Case C‑833/18 SI and Brompton Bicycle Ltd v Chedech [2020] ECLI:EU:C:2020:461, para 38.

[36] Case C-145/10 Eva-Maria Painer v Standard VerlagsGmbH and Others [2011] ECR I-12533, para 92.

[37] THJ Systems v Sheridan (n 12).

[38] See eg Andres Guadamuz, ‘Do Androids Dream of Electric Copyright? Comparative Analysis of Originality in Artificial Intelligence Generated Works’ (2017) 2 IPQ 169.

[39] Patrick Russell Goold, ‘The Curious Case of Computer-Generated Works under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988’ (2021) 2 IPQ 120.

[40] Söğüt Atilla, ‘Dealing with AI-generated works: lessons from the CDPA section 9(3)’ (2024) 19 JIPLP 43, 48.

[41] For more on this “artificial distinction” see Söğüt Atilla and others, ‘Oxford Intellectual Property Research Centre Submission for UK Intellectual Property Office “Open Consultation on Copyright and Artificial Intelligence”’ (SSRN, 2025) 54-56 (forthcoming).

[42] The UKIPO, ‘Open consultation’ (n 7) [155].

[43] The only case concerning CDPA, s 9(3) was Nova Productions Ltd v Mazooma Games Ltd [2007] EWCA Civ 219, which involved a video game, not an AI-generated output.

[44] Söğüt Atilla and others (n 41) 59-61.

[45] ibid 57-58.

[46] Söğüt Atilla (n 40) 51-54.

[47] Called as the “redaction stage” by P Bernt Hugenholtz, ‘Copyright and the Expression Engine: Idea and Expression in AI-Assisted Creations’ (2024), 5 <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4982516> accessed 21 February 2025.

[48] US Copyright Office, ‘Copyright and Artificial Intelligence’ (n 8) 11-12.

[49] ibid ii, 2.

[50] ibid 12-18.

[51] ibid 19-21.

[52] See US Copyright Office, ‘Re: Second Request for Reconsideration for Refusal to Register A Recent Entrance

to Paradise’ (14 February 2022) <https://www.copyright.gov/rulings-filings/review-board/docs/a-recent-entrance-to-paradise.pdf> accessed 29 March 2025; US Copyright Office, ‘Re: Zarya of the Dawn’ (21 February 2023) <https://www.copyright.gov/docs/zarya-of-the-dawn.pdf> accessed 29 March 2025; US Copyright Office, ‘Second Request for Reconsideration for Refusal to Register Théâtre D’opéra Spatial’ (5 September 2023) <https://www.copyright.gov/rulings-filings/review-board/docs/Theatre-Dopera-Spatial.pdf> accessed 29 March 2025.

[53] Feist (n 13).

[54] Thaler v Perlmutter et al, 1:22-cv-01564, (DDC).

[55] Thaler v. Perlmutter, No. 23-5233 (D.C. Cir. 2025). For a brief overview see Eleonora Rosati, ‘US Court of Appeal confirms human authorship requirement, including for AI’ (The IPKat, 20 March 2025) <https://ipkitten.blogspot.com/2025/03/us-court-of-appeal-confirms-human.html> accessed 29 March 2025. It should be noted that in this case the claimant argues that the author of the AI-generated image should be the AI tool as there was no human contribution whatsoever to the image and the AI tool created the work all by itself.

[56] USCO Public Records System (n 9).

[57] ibid.

[58] See Feist (n 13) where the selection, coordination, arrangement terminology is used for compilations, not artistic works.

[59] USCO Public Records System (n 9).

[60] For further details and comments on this decision of the USCO see Söğüt Atilla, ‘A single piece of US copyright: Are AI-generated images original artistic works or banal compilations?’ (The IPKat, 18 February 2025) <https://ipkitten.blogspot.com/2025/02/a-single-piece-of-us-copyright-are-ai.html> accessed 29 March 2025.